Asmaa Al-Rashed was born in Daraa Governorate in southwestern Syria and stopped receiving formal education when she married at the age of 14. She fled Syria with her husband and two eldest daughters in 2012 to the Zaatari refugee camp in Jordan.

Seeking a safe place away from the bombing and destruction, after two years of depression and losing hope and passion, Asmaa began to lift herself and her family, while also supporting her local community by reading stories to children, becoming an ambassador for the “We Love Reading” organization after receiving training to read aloud. Eventually, she published her own stories in the camp’s magazines.

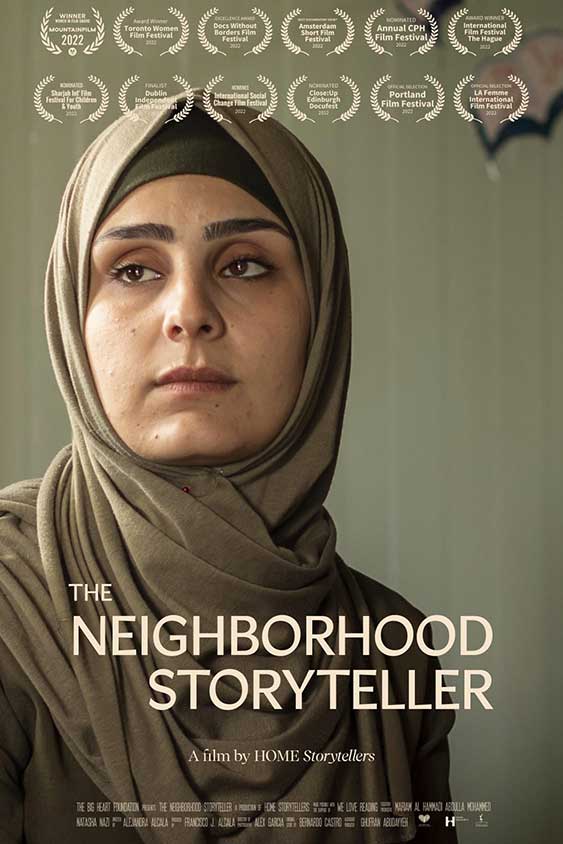

Her project “Let’s Read“, which focused on empowering teenage girls, was featured in the award-winning documentary The Neighborhood Storyteller (2022). Now settled in Nîmes, France, Asmaa spoke with “Qisetna” about her journey so far and her plans to continue advocating for girls’ education.

I believe that everyone has the ability to adapt and embrace change if they want to and make an effort to be part of the society they live in.

In the film, we see that you encourage parents, especially fathers, to allow their daughters to participate in the reading program. What was your family’s attitude toward reading and education when you were growing up?

My father was a primary school teacher, and of course, one of his messages was to encourage the education of children and people in general. I am lucky because my father wasn’t violent with me when I left school.

However, I couldn’t continue my education in a community that doesn’t encourage girls’ education, claiming it fears for them. There was no real motivation even in school when we went there.

We often received comments from the very few male or female teachers, like: “When will you get married and leave school? You won’t gain anything from this; in the end, you will go to your husbands.” Education was compulsory only up to the sixth grade, so many girls didn’t continue their studies. In general, parents didn’t care about educating girls as much as boys because they believed girls could take another path, such as marriage or becoming homemakers. Taking care of the home is also considered a form of education.

Film poster for The Neighbourhood Storyteller (2022). Photo © HOME Storytellers

Did you face similar challenges in educating girls in Zaatari Camp as you did in Syria?

Yes, parents in Syria brought this way of thinking with them to Zaatari Camp. However, humanitarian organizations working in the camps were strict with families to prevent child marriages and promoted more Western values. Early marriage is also not allowed under Jordanian law. All this pressure on parents caused a significant shift. However, many still believe that educating girls isn’t that important, so there’s still a lot of work to do, but things are progressing and changing.

What drove you to participate in the film and share your story?

Growing up, I had a talent for storytelling, although I was often mocked by my peers for frequently talking to trees, clouds, and nature. I was also a good listener to those around me, but I didn’t have many friends, and I was very shy and isolated, constantly bullied. But as I grew older and began to understand life, I realized that my behavior was seen as weakness, and I wouldn’t get opportunities in life if I remained isolated. I had to break the barrier of fear, especially because I was a girl.

Indeed, that’s what happened. After a few years, I had many friends, and I was always happy to listen to them, as they often came to me with their problems. I’m very passionate about encouraging people to listen and share stories with one another.

Over time, and through the organizations I worked with, I discovered the importance of storytelling, including my own stories. They were no longer traumas and weaknesses but became my strengths, helping me seize opportunities in life and revealing my true personality, which I love.

One story I particularly like to share is my early marriage, which I find especially important so that other girls can learn from it and be encouraged to share their own early marriage experiences.

Now, I feel no shame in sharing our stories, even if they are painful, because it’s a way to learn from each other. That’s why I consider the film my opportunity to make my voice heard to the world, especially to girls and women everywhere and from all social backgrounds. Additionally, the image that the media promotes about refugees often didn’t sit well with me because it portrays us in a negative light as weak people.

Yes, we are going through a phase of weakness, no doubt, but we need support and assistance more than pity and having sad photos taken of us or showing refugee children in undignified conditions. All these things deeply saddened me because the reality differs from what we often see in the media.

My children give me hope in this life, and as their mother and role model, I draw energy from them. Having had children at a young age, I often feel like their friend, especially with Tamara and Maya.

Which stories have impacted you the most?

As Asmaa, I haven’t isolated myself from what’s happening in Syria. Every day, I listen to stories of detainees online, and while this deeply hurts me, it also gives me strength from these heroes. It also makes me appreciate my own situation.

Additionally, the daily stories from walking around the camp and seeing how people’s lives have changed are impactful. Just seeing the conditions in the camp changes everything within you. One thing I gained from that environment is improving my reading habits. I used to read as a hobby, but now reading has become more than that. It has taught me how to live, how to communicate and engage with others, how to raise my children, how to interact with people, and how to defend the oppressed.

I was always searching for books that could change my life and inspire me. Stories like Malala Yousafzai’s, and how she fought for girls’ education, resonated with me. She accepted her struggles and overcame her fears. I also feel passion and inspiration when reading books by Adham Sharkawy, such as Letters from the Quran or Evening Talk.

Film screening of The Neighbourhood Storyteller hosted by the Robert Bosch Academy in Berlin. From left to right: Dr. Rana Dajani (founder of “We Love Reading”), Asmaa, and Alejandra Alcala (director of The Neighbourhood Storyteller). Photo © Anita Buck, Robert Bosch Academy.

I’ve been through experiences I consider traumatic—getting married young, moving from house to house, bearing the responsibility of the family, and being a mother were heavy burdens at that time. I believe it affected my mental health negatively to some extent.

I would always look out from my husband’s family home balcony to watch the girls returning from school, which was an image that always warmed my heart. Another moment that tested my strength as a girl and was shocking to me was when my father was arrested. It was a difficult scene to see my father detained by the Syrian regime forces.

We stood there, looking at him, unable to do anything. I remember my father smiling and saying, “This is the revolution, and the price must be paid for freedom.” Also, in the early years of our displacement in the Zaatari camp, I experienced a forced miscarriage of sorts. I didn’t know how to ask the doctors for treatment that would allow me to keep the child.

These experiences made me question my strength and how I could use it moving forward. So when the opportunity came to train with “We Love Reading” under Dr. Rana Dajani, I felt it was an unmissable opportunity, and I quickly signed up for the training. I now use all these stories to empower myself first and then strengthen my community because, in my opinion, those who can’t help themselves won’t be able to help the people around them at all.

You are using this strength now to help others. One way you’ve chosen to do that is by writing stories for children. Can you tell us more about that?

As I mentioned earlier, I received training from Dr. Rana Dajani and began reading stories to groups of children. I mainly read them fictional stories to transport them away from reality and encourage them to imagine. Afterward, the children would take the books home and read them with their parents. When they returned, they were more engaged with the story and would draw or color the characters.

Seeing their passion and enthusiasm made me think, why not write some stories myself? I wrote local stories focusing on the daily challenges we faced in the camps. I also used the children’s names for the characters, which made them very happy and increased their engagement. These stories were published in the camp’s paper magazine, The Path, and I became known as ‘The Neighborhood Storyteller’.

What is the meaning behind the magazine’s name?

It’s about looking toward the future and reminding children and young people that they have a path to follow. That’s my interpretation. But according to the magazine’s director, the name was chosen to instill in our minds that the camp is not a permanent place to live; it’s just the path to home. I also contributed to a digital magazine called The Kite, where I proudly published a story titled The Girl with the Yellow Hair. I was happy about this contribution because I knew these stories were reaching children in northwestern Syria. That was important to me.

I used to read as a hobby, but now reading has become more than that. It has taught me how to live, how to communicate and engage with others, how to raise my children, how to interact with people, and how to defend the oppressed.

You received a grant to launch a project in Zaatari Camp. What is this project?

The idea began in 2016. Some of the girls who participated in reading activities stopped attending when they reached the age of 12 or 13 because they felt they were too old for these sessions. I felt sad about this, so I took it upon myself to start other projects like Let’s Read to encourage girls’ education and also provide psychological support for them. My home became a safe space for them. I continued this project until I moved to France in 2022.

Then I connected with Abheejit, the founder of Ekatra, a company in India that works in technology. We are both members of the Catalyst 2030 network. He suggested we collaborate to improve internet access in the camp and launch my project innovatively, tailored to the camp’s needs.

I applied for a grant from the Refugee-Led Innovation Fund to finance the project. I decided to set up this project in Zaatari Camp because I have a network of people there, like teachers, who can help implement it.

This project will begin in September 2024, and it will be an educational platform capable of working with weak internet connections and easy to use offline. The project will serve middle school students and girls who are not in school. If the project succeeds, we can apply for additional funding to support more students and even parents who can benefit from it. It’s a community-driven project and adaptable to very difficult conditions.

Asmaa leads a reading circle in Zaatari Camp.

How have you and your family adjusted since moving to France?

I believe it’s not easy for anyone to adapt to a third country and re-establish a new life, and people often suffer from depression because of it. But as a family, we were aware of where we were going and knew it was a society different from our Arab communities. Also, as a veiled woman, I was mentally preparing myself to deal with any situation that might arise against me anywhere.

However, I’ve now been living in France for about a year and a half and haven’t encountered any unpleasant or racist incidents. I feel like I’m living in a kind and welcoming society that accepts refugees comfortably. Sometimes, I feel misunderstood due to my lack of fluency in French. It was easier for my children because they mastered the French language and integrated faster. I believe that everyone has the ability to adapt and embrace change if they want to and make an effort to be part of the society they live in.

Indeed, I’ve started doing this by attending language schools, participating in support programs for migrant mothers, and organizing initiatives with Tamara and Maya in their school. This has helped us a lot, and I think it also helped the teachers and migrant students. It’s important to understand each other’s backgrounds and consider the circumstances from which migrants came. This encourages teachers to accept the random behaviors of some students and try to help them overcome the past and move forward for their future.

I won’t deny that I miss my busy life in the camps, especially since I was a leader in social work and always in contact with the community, women, and children. But now, I focus more on integration and understanding this new society. I discovered that the busy life in the camps isn’t much different from that of refugees in Europe.

People’s feelings are almost the same, so I’ll try to apply the same things I used to do with refugee girls in France and create a safe space for them to talk. I also want to engage with parents. I’ve heard some stories about fathers saying that when their daughters reach the age of 14 or 15, they feel that Europe is not the right place for them. I don’t agree with that. So, I want to build communication between children, parents, and even schools, as well as between refugees and French society.

This is the plan I’m working on. And, of course, I now have many French friends.

How are you working to achieve this goal?

I’m working hard to master the French language, which will be crucial for continuing my work in France. I’m also learning about the situation of migrant and refugee children, especially their experiences in the educational system here, so that I can use this knowledge later. I’m also forming friendships within the French community, and I already have some great friends. I try to join community initiatives that benefit me as an individual, and as I mentioned earlier, I’ve started organizing initiatives with several schools, such as screenings of The Neighborhood Storyteller film.

The mother is the foundation of building a healthy and thriving society. The mother is the teacher, the school, and the entire community, so we must have aware and inspiring mothers.

How do your children inspire you?

My children give me hope in this life, and as their mother and role model, I draw energy from them. Having had children at a young age, I often feel like their friend, especially with Tamara and Maya. I want to teach them our Arab culture in the right way that makes them strong individuals with ambition in life. It pains me when people justify certain behaviors based on Arab traditions, like depriving girls of education in the name of customs and traditions.

This leads to uneducated mothers who don’t know their rights under the guise of tradition, resulting in an ignorant and weak society. In my belief, and the belief of many others—even within our religion—the mother is the foundation of building a healthy and thriving society. The mother is the teacher, the school, and the entire community, so we must have aware and inspiring mothers.

Tamara inspires me greatly when I see her planning her future on her own and acting beyond her years. She often recommends books to me after reading them, and her choices are always wonderful. She’s also very interested in psychology.

Maya inspires me with her love for life, passion for learning languages, and love for travel and new experiences. She has many friends and believes that good friends are important because they are a source of strength for her.

Mohamed inspires me with his willingness to try any kind of new food. He stands out for his intelligence and quick learning. He loves the Arabic language very much and also enjoys the atmosphere of a big family.

Madeleine inspires me with her calm demeanor and her ability to achieve what she wants without making much noise. She’s very elegant and takes great care in organizing her things.

I try to learn and adopt a good quality or habit from everyone I know. My children are also an inspiration to me and support me in my professional journey.

Qisetna encourages those who are inspired by Asmaa’s story to take the We Love Reading online training and become We Love Reading ambassadors, just like Asmaa. This free training programme can be accessed here.

Writer: Nesreen Yousfi

Translator to Arabic: Juanna Anez