In the winter of 2019, Syrian-Armenian-American theatre and film artist Sona Tatoyan travelled to her family’s abandoned home in war-torn Aleppo, Syria. Her goal: to retrieve a treasured piece of her heritage — the over 100-year-old Karagöz shadow puppets crafted by her great-great-grandfather, Abkar Knadjian.

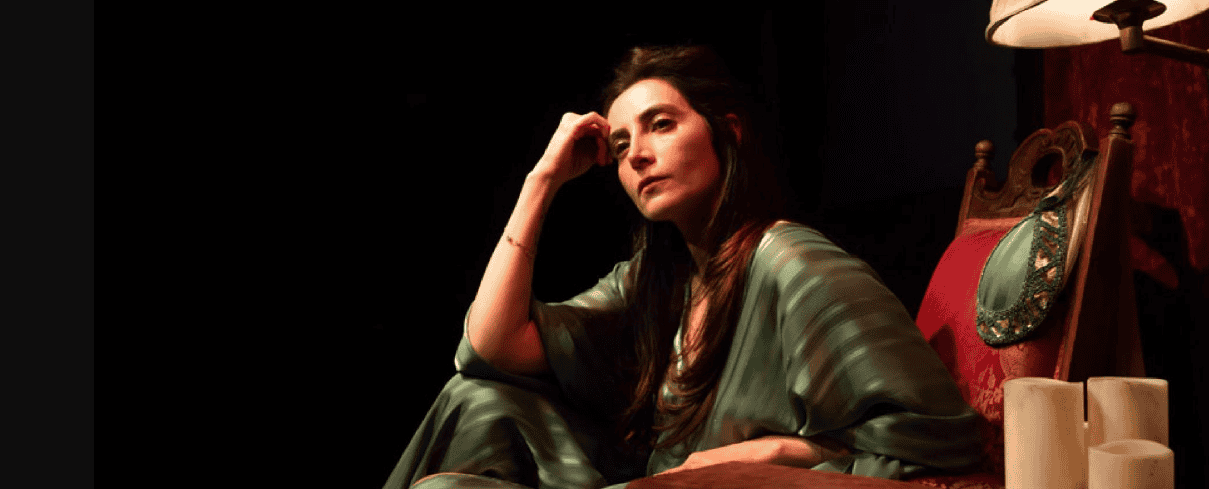

Stage in Scales Fine Arts Center, Wake Forest University. Photo © Sydney

Bowman and Julian Glasthal.

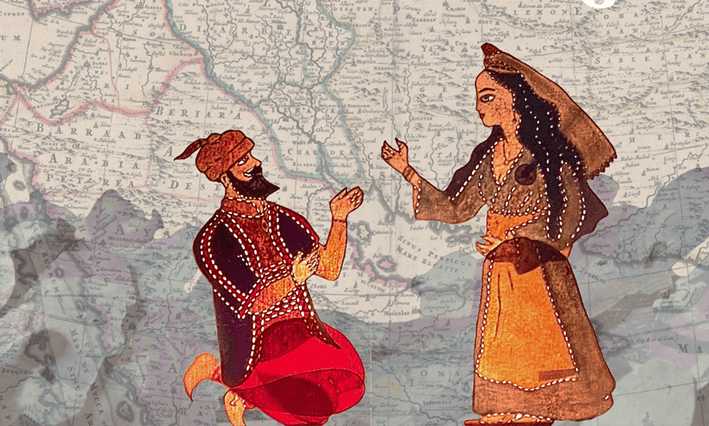

These colourful, flat figures once starred in captivating Karagöz puppet shows —a form of “cinema before cinema”— orchestrated by Knadjian, a skilled puppeteer and hakawati (“storyteller”) from Urfa (Şanlıurfa), entertaining audiences in coffeehouses across Southeast Anatolia. However, in the wake of the Armenian Genocide in 1915, Knadjian and his family were forced to flee their home, taking the puppets with them on a perilous journey from Urfa to Antep to Aleppo. Safely tucked away in a wooden trunk in an attic, these puppets bore silent witness to a century’s worth of family history and the tumultuous Syrian War raging outside — until their remarkable rediscovery by Tatoyan.

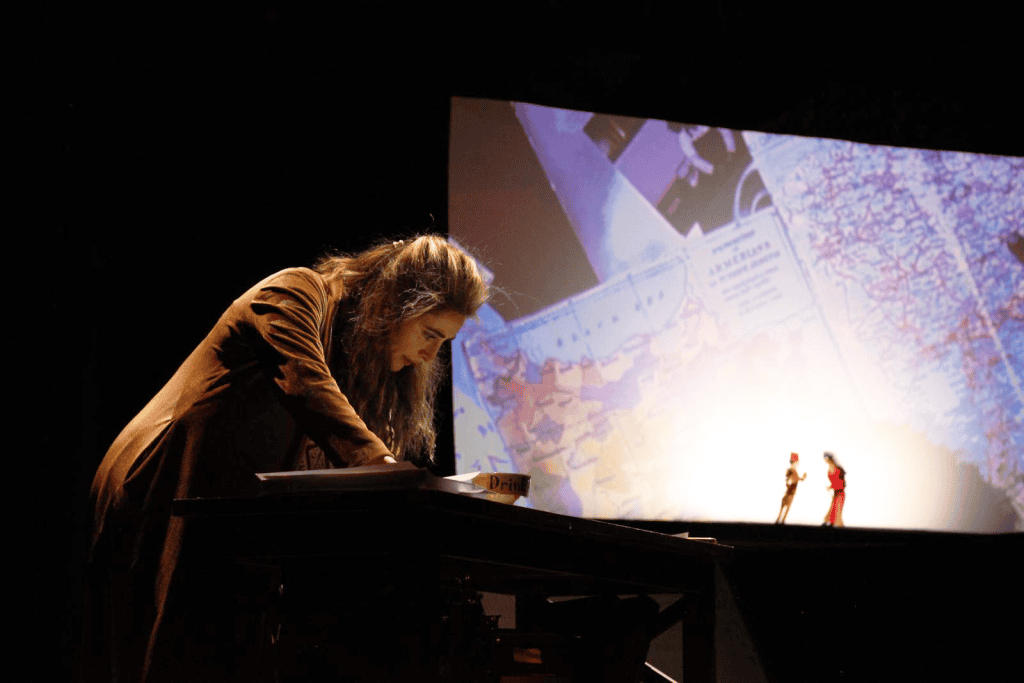

Tatoyan hoped to find a handful of surviving puppets, but instead, she unearthed over 180, including house puppets, tree puppets, cows, horses, snakes, and more. This nearly surreal experience — uncovering a “magic box in a war zone”— inspired her to create Azad (“free” in Armenian, Farsi, and Kurdish), a live performance in two variants: Azad Storytelling and Azad (The Rabbit and the Wolf). Both renditions feature indigenous Middle-Eastern folk music, traditional Hakawati storytelling, and, of course, Karagöz shadow puppetry; The Rabbit and the Wolf iteration, a work-in-progress ‘multimedia theatrical experience’, also includes video projection and movement, gearing up for a major world premiere.

A Thousand and One Nights-esque “story within a story within a story”, Azad seamlessly merges fiction with non fiction, with Tatoyan (akin to Scheherazade) intricately weaving multiple narratives together, while the puppets serve as both her guides and antagonists.

You’ve described these puppets as survivor objects, a term coined by Heghnar Zeitlian Watenpaugh to describe artefacts that have withstood a calamity. Typically, such traumatic events can significantly alter an object’s materiality — they may break, crack, and so on. Considering this, what was the physical condition of your shadow puppets upon discovery? Did they require restoration before being utilised in the Azad performance?

No, actually! They were in pretty great condition. The thing is that Aleppo is dry, and so they were in a dry environment, in a trunk, in a dark attic. So, the conditions were prime for them to stay well-preserved. There are about just under fifty of them used in the show currently, and we haven’t done any restoration work on them — they’re used as is!

Regarding the shadow puppets being survivor objects — it’s fascinating that their original function remains unchanged. The experience of trauma often transforms the original purpose of survivor objects, yet your puppets continue to serve as storytelling tools through Azad. Was the decision to preserve their original function always set in stone, or did you ever consider, or perhaps still consider, donating them to a cultural institution for display as works of art? Or using them differently?

When I found them, I never thought I would be performing with them — that’s something that has been an organic process. I’m an actor, and a writer, and a performer, but I didn’t think that I was going to be performing with puppets; that was never on my agenda. As far as using them differently, many different things are rolling around: we have a proposal put together for a book (‘ScherAzad’) on the collection, working with different historians and scholars on each of the puppets and the history of them and so forth, and there have been talks of exhibitions with different museums, and that’s ongoing. But, as far as donating them anywhere, we’ve been wanting to keep them in the family.

puppets in the attic of her abandoned ancestral home. Photo © Antoine Makdis.

The Karagöz shadow puppets, of course, are just one component of the performance — Azad is described as a ‘multimedia theatrical experience’, featuring also indigenous Middle Eastern folk music, traditional Hakawati storytelling, video projection, and movement. Could you share any challenges you encountered in bringing together these diverse elements into a cohesive live performance?

Again, it’s all been so organic. There was never an ‘I’m going to make a multimedia theatre performance’; there was never an agenda that I went about systematically doing. I consider myself a weaver — as a storyteller and as an artist — weaving a lot of what may seem disparate things. In my culture, I embody this also: I’m a first-generation Syrian-Armenian-American. I grew up straddling these very different, often diametrically opposed worlds, and [I] weave and bridge them all. I think my work is like that.

The other piece of it that’s really embedded in all of this is A Thousand and One Nights; there is a strong foundational presence of that in the work. The Nights, in itself, as a piece of storytelling and literature, is a story within a story within a story; it is different kinds of stories: fables, morality tales, fairy tales, erotic tales…there’s poetry. So, in a kind of mirror and echo to that, there is live Oud, Karagöz puppetry, my performance, multimedia projection, and the auto ethnographic work I’ve been doing for twenty years, all woven together. But it’s all very organic; it was never a set, methodical intention that I was going to do it this way. Oftentimes I say that I didn’t even write this; it’s been writing itself, or it’s the puppets writing it, or the spirit of my great-great-grandfather.

The show’s mixed media production — integrating projections, specialised lighting, and classical Middle Eastern music interwoven with sounds recorded in Aleppo — purposefully creates an immersive and multi- sensory experience for the audience. What inspired your decision to pursue this sensory-rich approach in your production? Did you anticipate that it would enrich the storytelling aspect of the performance?

I think it’s living in this space that I’ve lived in my whole life, in terms of straddling cultures. I was born in Baltimore, Maryland, on the East Coast, and I grew up in small-town America: in small-town Alabama, in small-town Indiana —very American. And then, every summer, we would go to Aleppo and be with my mother’s family, so you couldn’t get a wilder difference. And, I think there was always this thing of being an outsider-insider in these places; when I was in Syria, my sisters and I were ‘American,’ and here [U.S.] we were ‘Armenian-Syrian-Middle Eastern,’ so there’s never been a full belongingness in either place.

So, when I would think of Syria, the sounds and the smells, all of those things were so different — it was like The Wizard of Oz when Dorothy goes to Oz, it becomes technicolor; that’s how it felt, dropping in from this world to that world. As an artist and storyteller, what you’re trying to do is impart a feeling. You want to create a sense of empathy in those who are receiving, ingesting your story; for them to really comprehend in totality, as much as possible, the experience you’re trying to relay. Those sounds, those smells are a part of that world, they’re hard to parcel out —so, the immersive quality of it [Azad] was very important.

Delving into the storytelling aspect of the show, it’s intriguing how the stage play deliberately embraces a nonlinear or disjointed narrative — there is constant changing of subject matter, the merging of fictional and non-fictional events, and the inclusion of abrupt breaks. Can you shed light on what drove your decision to adopt such a distinctive narrative technique? And were there any concerns about potentially confusing the audience?

My friends and colleagues would say that’s how my mind works! But, it’s also very Nights like — again, the whole story within a story within a story; she’s telling one story, and a thread from that story links to the next thing, and you don’t know what’s going to cross and intersect what. So, in that way, I think I have a mind like that.

I’ve been, sort of, intuitively working towards writing this for twenty years…and from the outside, it looks like there’s no order to it. There is this fragmentation, but it’s deliberate fragmentation. Our part of the world is broken up —the earthquake that happened a year ago in literally that same part of the world, southeast Turkey, Aleppo, which are the same regions I talk about; my ancestors were form Antep (Gaziantep), Urfa (Şanlıurfa), the same towns, pre Genocide, that the piece is about. So, there’s this whole: the land is broken, the people are broken, the history is broken, and [I’m] trying to put it back together. So, this could never be a linear exploration.

As the sole actor and narrator for the majority of the show, you bear a significant responsibility in keeping the audience engaged. Did you find this task daunting, or did it perhaps invigorate your performance in some manner?

I’ve never thought about it as ‘daunting’ — I feel it as exhilarating. Again, I’ve spent half of my life working to tell this story, and while I may be the only human actor you see on stage, the puppets are the antagonists in this story in many ways; they’re the other characters. So, it’s not a solo performance in that traditional sense. It’s very much a play in that there’s me and there are other characters that are doing things to me; we meet, and things happen as a result of that meeting. This is what I love to do; it’s a lot, it’s huge — I’m not going to deny that — but it’s fun!

You began writing Azad in 2021 and performed it in 2022. Since then, you’ve presented it multiple times in various locations, most recently at the Scales Fine Art Center at Wake Forest University in February 2024, under the title Azad (The Rabbit and the Wolf). Can you explain how this latest iteration differs from the original version, Azad Storytelling?

The Azad Storytelling piece began as a lecture I gave at Harvard University in 2019. I gave the Hrant Dink lecture at the Center for Middle Eastern Studies, and that was in many ways the genesis of what became Azad Storytelling. It was originally part of a project that I co-created called 1001 Nights in Los Angeles. The first performance of what would become Azad was done at that event in August of 2021. It wasn’t yet called Azad; it was called ‘1001 Nights Storytelling,’ but it was essentially the same piece that became and was named Azad Storytelling. So, that was the very first performance.

These puppets have given birth to so many different things, and it makes me chuckle because that is the Nights.

Then, in the spring of 2022, Hakawati — my non-profit — produced a series of five Azad performances in April (at The Pico Playhouse), coinciding with the Armenian Genocide commemoration. There was interest in that, so there were invitations to perform it: [at] NAASR in Boston, and a non-profit in Berlin got in touch with me, and I got an invitation to go and perform in an event around ancestry and storytelling, and so forth. In the meantime, my really dear friend Bill Pullman, who’s been a big supporter of the project and is on the board of my non-profit, helped us get in touch with a great theatre in New York City called The Vineyard Theatre, which has produced some incredible plays.

The artistic director of that theatre (Sarah Stern) very much responded to the story in Azad, and we began to talk about how to convert it from a storytelling piece into a theatre piece — which is just a different medium. The Vineyard gave us our first workshop in January of 2023, and then the University of Connecticut gave us the next one. Then, Harvard ArtLab, and Wake Forest was the last one. During that year of intense development — with workshops and residencies — the piece kept growing and evolving, becoming more and more of what it was in its theatrical form. And, story-wise, it was also growing; my relationship with Osman Kavala is very much a part of Azad (The Rabbit and the Wolf), which does not exist in Azad Storytelling. So, it became necessary to make that distinction: Azad Storytelling exists as a forty-five-minute storytelling piece, meanwhile The Rabbit and the Wolf is on a trajectory towards a major world premiere as a piece of theatre. It will have a performance in New York and then eventually tour cities in the U.S. and also internationally.

I believe the next development residency is scheduled for September 2024 at M.I.T. Is that correct?

That was what was supposed to happen, but we are now in talks with a theatre. We had our first thing at Vineyard, which is a professional theatre, and then we were at UConn, Harvard, and Wake Forest. We know now, with everything we’ve learned in this year of development, that we have one final workshop left to finalise the script and everything. We were going to do it at M.I.T., but as we kept talking and going, “Okay, if this is our step towards our world premiere,” and being approached by various theatres, it began to make sense to do this final workshop in a professional theatre — as opposed to in an educational space — for it to be the springboard to the world premiere. So, right now, we are in talks with a couple of different theatres, and we are weighing what’s the best thing in terms of supporting this last piece of development for the piece.

I suppose, then, after this final development, the performance will become standardised, and there won’t be any more versions.

Yes, that’s right. The thing is, with a piece like this, it is not something you just sort of sit down, page one, write…write…write by yourself, and then go up and do. Because of the nature of its multimedia and all the different pieces in this orchestra — the puppets, the Oud, me, the projections, the video, the soundscape, all the pieces that fit together — it’s in these residencies where the massive leaps are taken. My collaborator and director, Jared Mezzocchi, and I work together, have these writing sessions, learn from each of these things, and go into the next residency with a new script. But then in that week of residency, when it’s on its feet, with all the different elements, things are changing. It’s like a recipe you’re putting together; you’re like, “Oh no, too much salt!”

As an artist and storyteller, You want to create a sense of empathy in those who are receiving, ingesting your story.

The nature of the piece is that it needs to evolve and be developed on its feet; that’s where we’re learning and getting the feedback. And, an integral part of that has been the audiences also, because in each of these spaces, we present the work, and it’s through their responses that alterations are made. So, it’s that feedback loop which has helped to grow the piece in each of these iterations. All that to say, there will be three performances at the end of this [final] two-week workshop, and that feedback will be a part of: “Okay, this is it, we’re locked, script locked, this is the thing, and now we’re ready to premiere it in the world.”

Lastly, regarding future projects scheduled for this year, it appears that Azad will extend beyond the stage with the #BeAzad Campaign — a multi-platform online campaign inspired by the message of Azad to “Be Free” and “Reframe your story”, set to launch in 2024. Could you share any insights about this project?

Yes, it is set to launch in October of 2024. We’ve been invited to work with Stanford Medical School, so that’s where it will launch this coming fall. It’s a response to the piece Azad; Every time I have performed either Azad Storytelling or Azad (the rabbit and the wolf), there has been a real hunger to have conversations afterwards. It has inspired dialogue and has really catalysed audience members or the receivers of the work to want to share their own stories of how to reframe their own dark experiences in their lives, which they’re now able to see from a wider lens, in a more holistic perspective. So, we are launching this BeAzad Campaign this fall, and we’ll be collecting and recording people’s stories to share on an online platform. These puppets have given birth to so many different things, and it makes me chuckle because that is the Nights. The Nights are iterative; there’s technically no end to the stories in the Nights. It’s a thousand and one, not because that’s an exact number, but because the idea is that it continues.

Azad Storytelling graced the stage in Armenia on June 30, 2024, as part of the ‘1001 Nights’ experience, co-created with Isaac Saboohi and produced by Hakawati.

Hakawati, a non-profit organisation, was founded by Syrian-Armenian-American actress, writer, and producer Sona Tatoyan in honour of her great-great-grandfather’s work. Its mission is to amplify the voices of communities that exist on the frontlines of suffering, utilising the transformative power of storytelling to facilitate healing from trauma.

Interview by Karine Khachatryan